How the runes went from Hassela to Minnesota

The Kensington Runestone, which was found in the Swedish settlements of Minnesota in 1898 by the immigrant Olof Ohman, is perhaps the world’s most famous and controversial runestone. A majority of scholars dismissed it early on as a fake, but it has remained an unsolved mystery. In 2019, a middle school teacher and her fourth grade in Hassela in Hälsingland helped to shed new light on the strange runic alphabet used on the stone.

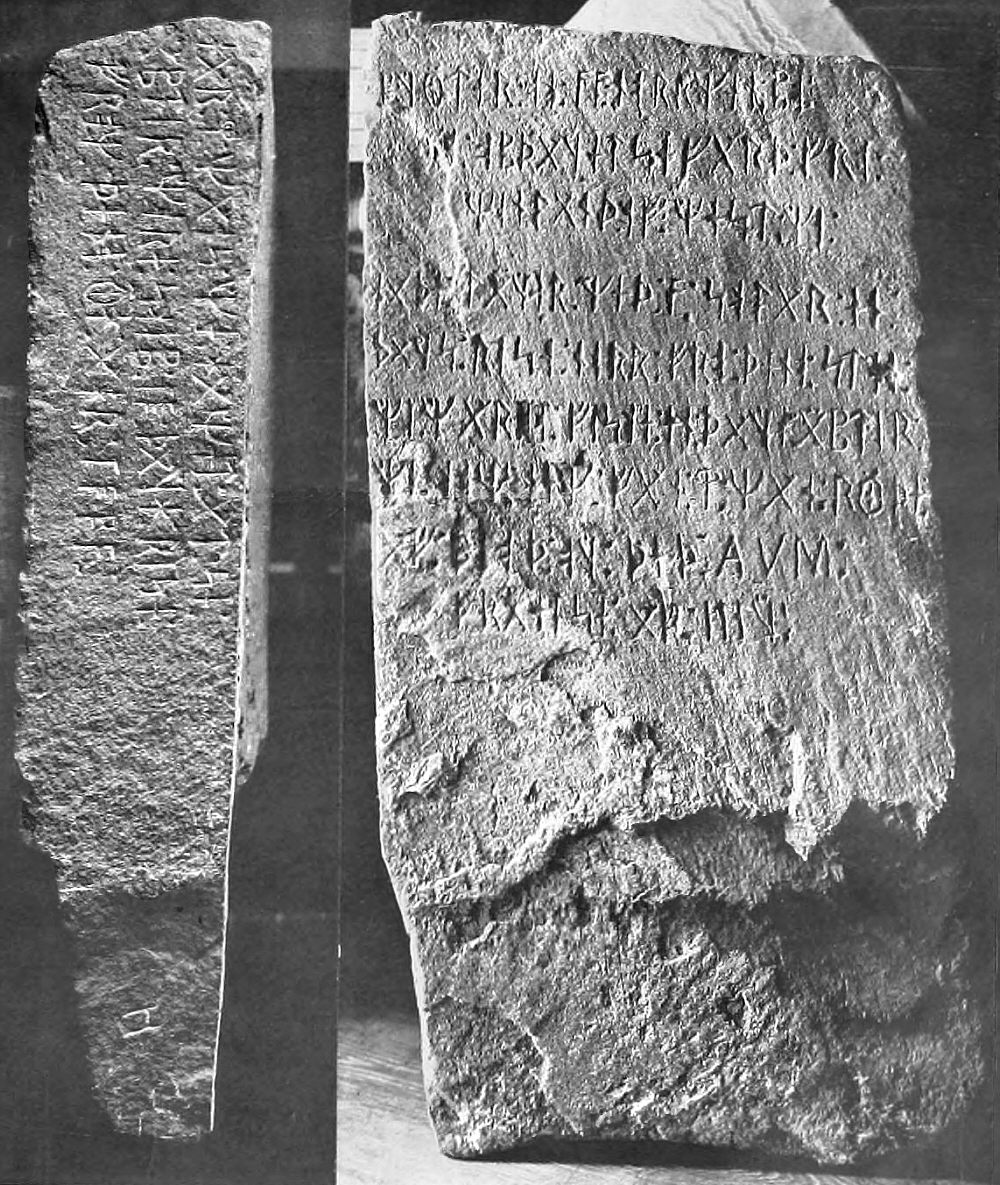

The runic inscription on the Kensington Stone contains a statement that eight Götalanders and 22 Norwegians were on a voyage of discovery and erected the stone in 1362. The strange runes on the stone had not been documented before and were therefore called “Kensington runes”. If the dating on the stone were correct, it would require the history books to be rewritten, as evidence that Scandinavians travelled much deeper into the continent than the previously known landings on the east coast of North America. Many people would still like to believe that this was the case.

The mystery of the Kensington runes

Magnus Källström does not believe it. He is a runologist and associate professor of Scandinavian languages at the National Heritage Board. His work at the Board involves interpreting runic inscriptions and putting them into their historical context. For a long time he took no interest whatever in the Kensington Runestone.

“The writing on the stone mixes Swedish, Norwegian and English linguistic features, and it is obvious that it uses more modern word forms. There was no runic system like this in the Middle Ages. However, we now know that there was a similar set of runic characters in the late nineteenth century, at least in Hälsingland and Medelpad,” he says.

It is only in recent years that Magnus Källström and other runic experts have been able to ascertain where the runic characters on the stone really came from. The first breakthrough came in 2003 when the stone was lent to the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm. Then the linguist Tryggve Sköld at Umeå University was able to link the runic alphabet on the stone to a probate inventory from Dala-Floda in Dalarna. Handwritten sheets dated 1883 and 1885 contained similar runes, but with slight differences. It was the first time that the set of runes on the Kensington stone could be linked to other writings.

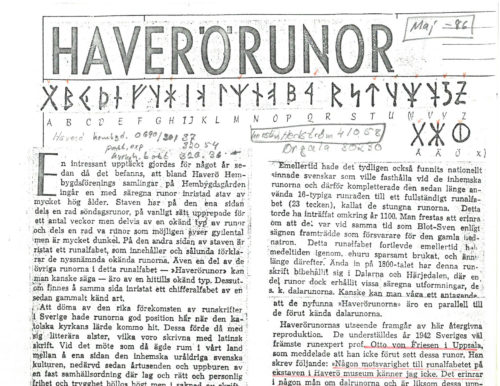

The Haverö stave provided the next evidence

In March 2017, Magnus Källström was going through a box left to him by the previous runologist at the National Heritage Board, Helmer Gustavson. Among the papers and binders he found a photostat copy of a newspaper article from 1944 with the headline “Haverö runes”. Magnus felt his pulse racing when he saw the runic alphabet.

“I immediately saw that it was the Kensington runes. The runes were transcribed from a runic stave that was said to be in the local heritage museum at Haverö in Medelpad. I telephoned immediately and was told that they still had the stave. From never having cared about the Kensington stone, I became extremely interested in it,” he says.

In October 2017 he was able to visit the local heritage museum. The stave, which turned out to be a measuring stick, contained exactly the same runes as the Kensington stone. The fact that they were carved on a stick for measuring one aln (about 2 feet) also gives a dating in itself. The aln was abolished in Sweden in 1889 when the metric system was introduced. The runic alphabet on the Kensington stone had thus been used in the area around Medelpad in the 1880s, just over a hundred kilometres from the place where Olof Öhman lived, before he emigrated to Minnesota to become Olof Ohman.

The devil at Ersk-Mats farm

At the same time, the teacher and rune enthusiast Anna Björk was at home in Hassela in Hälsingland, thirty kilometres from Haverö, thinking about the Kensington Runestone. She had read Mats G. Larsson’s book from 2012, “Kensington 1898: The runic find that baffled the world”, and for twenty years she had also tried to decipher the runes in the farmhand’s room at the Ersk-Mats farm in Hassela, which appeared to be indecipherable. Ersk-Mats is part of the UNESCO World Heritage site known as the Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland. The runes at Ersk-Mats came up when she was teaching her school class about the Viking Age.

“I told the pupils, ‘Those runes can’t be deciphered.’ Then when I read Magnus’s article about the Haverö stave, something clicked in my head. Everything fell into place, and I told my pupils, ‘We’ll do it tomorrow’,” she says.

With the help of the runic alphabet from the Haverö stave, it did not take Anna and the children many minutes to decipher what was written on the ceiling of the farmhand’s room: “Diefvulen” (the devil). There was also a name: “Hans Olofsson”.

“A shiver ran through my body, to say the least. Then it turned out that the guide on the farm had similar runes in his barn nearby, where two more names were written.”

Anna Björk contacted Magnus Källström and Mats G. Larsson, and together they managed to decipher the names in the neighbouring barn, written in the same type of red chalk as in the farmhand’s room at Ersk-Mats. Moreover, they were dated 1870 and 1877 respectively. These are the first documented Kensington runes dated before 1879, when Olof Ohman emigrated to America, and 28 years before the Kensington Runestone was unearthed.

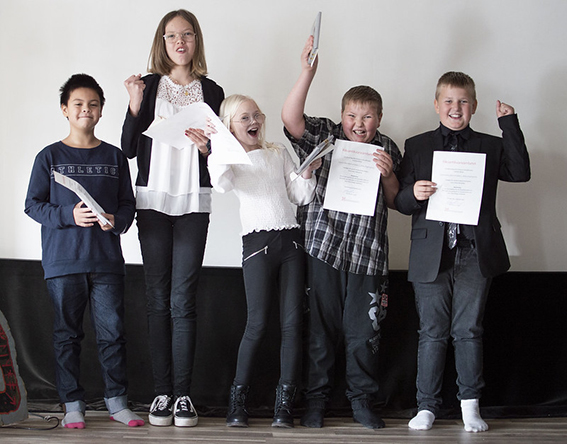

An award to the fifth grade

A radio programme about history, “Historia i P1”, and a television news programme for children, “Lilla Aktuellt”, made a pilgrimage to Hassela to tell the story of the 10-year-olds who deciphered the runes. And in October 2019, just as the pupils were about to start the fifth grade, the director of the National Heritage Board turned up in the company of Magnus Källström to award the National Heritage Board’s Medal of Merit to Anna Björk and her fourth-grade pupils for their discoveries.

“The medal of merit is the biggest thing that has happened to me, but the children probably felt that the highlight for them was when they were on ‘Lilla Aktuellt’ and a question in the radio quiz show ‘Vi i femman’ was about them,” says Anna as she laughs remembering the sensational event and the fact that adults and children have different perspectives on life.

The tracks lead on to America

Anna Björk has continued searching the archives for the three names that are written in runes in Hassela. She has managed to track down one of them: Olof Danielsson Oskar, who took the name Osher in America.

“I searched and searched among thousands of names in the records and eventually I found him. Unfortunately, he died of pneumonia three months after he arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota. His wife Karin remarried another man from Hassela, William Ward.

Anna’s next goal is to travel to the United States and Isanti, where many of the people from Hassela settled. These plans are temporarily on hold due to the global corona pandemic.

“I’m sure there are more Kensington runes. Whenever I go into a barn around here, I head straight for the walls and check using oblique light from a flashlight. My dream is to go to Isanti, to seek out distant relatives and search through old barns with a flashlight there too.”

We may never know who carved the Kensington stone itself. Possibly it was Olof Ohman, possibly someone close to him. Another possibility is that it was someone who wanted to make fun of Ohman. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that the knowledge of the Kensington runes came to America with the wave of migration in the late nineteenth century from the region of Hälsingland and Medelpad.

Further reading

Here at Raa.se and at K-blogg.se, the Swedish National Heritage Board has published a number of articles in recent years about the Kensington Runestone and the runic alphabet of recent centuries. Here is a list of links in chronological order (in Swedish).

26 Nov 2017 Haverörunor – nyckeln till Kensingtonstenens gåta?

9 Sept 2019 Kensingtonrunor i Hälsingland

30 May 2019 Fler Kensingtonrunor i Hassela

30 Sept 2019 Skolklass löste runornas gåta – får Riksantikvarieämbetets förtjänstmedalj

9 Oct 2019 Hasselarunor och andra runor – kort föreläsning av Magnus Källström i samband med medaljutdelningen

Articles in English:

The Haverö runes – the key to the mystery of the Kensington Stone?

Kensington runes in Hälsingland