Kensington runes in Hälsingland

I often say that my job mainly involves reading and deciphering runes and that this can both be easy and extremely difficult. Sometimes I can see at once what it says and can translate the inscription on the spot; in other cases I have been forced to admit – even after spending a long time describing and thinking about an inscription – that I can’t understand a thing. The joy of suddenly penetrating an inscription of the latter kind is, of course, immense, but it is at least as great when someone else does it.

This article was published in Swedish on march 9, 2019

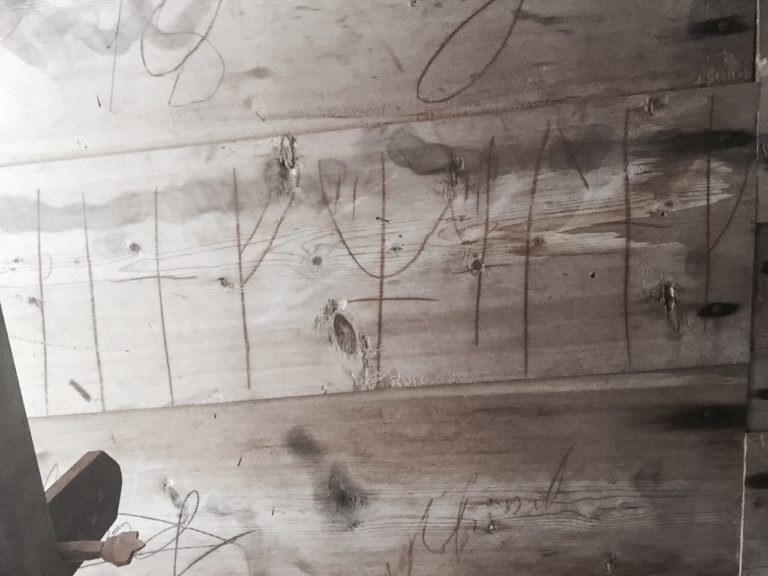

I experienced that a month or two ago when I received an email from Anna Björk, lead teacher in Hassela in Hälsingland. The email was about some runic inscriptions, of which I had previously had only the vaguest idea. They were written with two different pens on the ceiling of the farmhand’s room on a farm called Ersk-Matsgården in Hassela and they have been considered indecipherable.

Anna writes in her email that she was teaching the fourth graders about the Viking Age and had told them about the runes on the ceiling at Ersk-Mats. The pupils thought that they should try to interpret them together. Anna had replied that no one so far had succeeded and that it was probably just something that someone had scribbled on the ceiling.

Late that night, however, she gave it a try. She sat down and studied some pictures that she had in her mobile phone and wrote down the runes on a sheet of paper. She then remembered a K-blog post that I had written about the Haverö runes a couple of years ago. At first she could make no sense at all of the runes on the paper, but after eating a couple of ham sandwiches she suddenly realized what it said:

diefwelen

hansilffsn

“The devil feels right,” she writes about the first word, but the other word was harder to understand and a third word seemed incomprehensible.

In the history class the next morning, the pupils tried to interpret the runes by themselves and discuss what the inscription might say, and evidently they succeeded quite well. They thought that the second word must be a name. The question to me in the email was whether I could help with the interpretation of this sequence of runes.

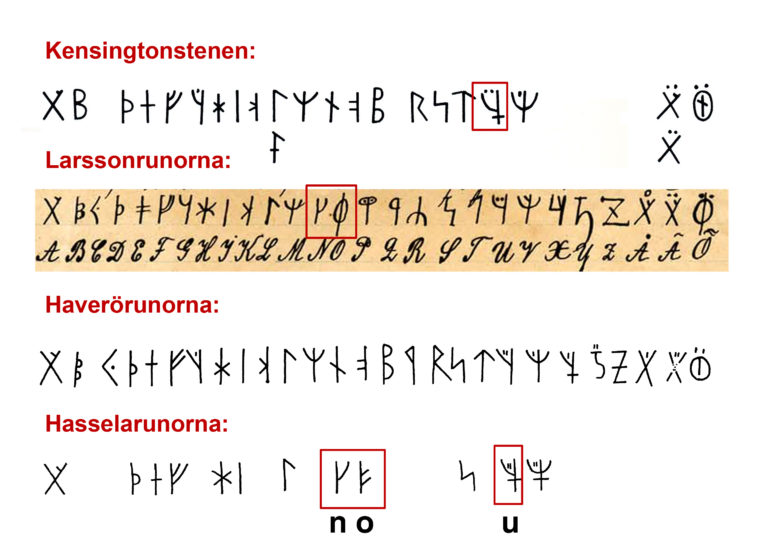

When I saw the pictures, I realized that the interpretation of the first sequence of runes was completely obvious. There is no doubt that it says diefvulen, written with the same type of runes as on the measuring stick from Haverö, which are turn are the same runes as on the controversial Kensington stone in the United States.

I was already vaguely familiar with the runes at Ersk-Matsgården because I had once seen a drawing of them in the archive at Runverket, which is said to have been sent in by the County Museum in Gävleborg in 1982. This was long before my time at the National Heritage Board and I don’t know what my predecessors have said about these runes, but I suspect no one realized that these are actually Kensington runes. The reason is no doubt that the characteristic a-rune is missing in this rune sequence and that the strange u– and v-runes can easily be mistaken for m-runes if read in haste. I had made the same mistake myself.

On the other hand, we had no previous information about the second inscription at Ersk-Matsgården. It consists of the same type of runes and also contains the characteristic cross-shaped a-rune, which is actually found only in this runic alphabet. Here I think the pupils in Hassela are absolutely right in thinking that it is a personal name. First it says hans, i.e. Hans, and then my guess is (o)lofsn, which must be Olofsson, although in the photograph I cannot really see whether the first rune really is an o.

The third inscription, in contrast, is not at all difficult to understand. It says ioos, which must be the customary initials for a name like J(an) O(lof) O(ls)s(on) or something of that kind. According to the drawing from 1982, there are other such initials inscribed in runes on the ceiling: lens and his.

With the interpretation of the runes in Hassela by Anna Björk and her pupils, we can add another instance of Kensington runes in Sweden to the previously known cases: the yoke from Månsta in Älvdalen, the runic alphabets left by the Larsson brothers from Dala-Floda, the paper with a runic alphabet owned by Gerda Werf in Älvdalen and the measuring stick from Haverö in Medelpad.

The very best thing about the Hassela runes is that the character set is not completely identical to any of the previously known variants. The rune for o has the side strokes to the right instead of the left and the n-rune has the form of a Viking Age k-rune. The latter variant is also found in the Larsson brothers’ runic alphabet and has been assumed to be due to a mistake, which it probably is not. The fact that the rune has this form shows that the runes in Hassela cannot have been taken from any newspaper article about the Kensington stone, since the stone has an n-rune of the normal type. However, the rune for u – where the form varies slightly in all the previously known occurrences of this runic alphabet – is identical in Hassela and Kensington!

I do not know how old the runes at Ersk-Matsgården are, but the farm was not built until the end of the eighteenth century. The dates 1868 and 1882 are also said to be inscribed on the ceiling of the farmhand’s room. How these relate to the runes remains to be investigated, but it seems reasonable to assume that the runic inscriptions also belong to the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The man who found the Kensington stone, Olof Ohman, came from Forsa in Hälsingland and there have always been suspicions that he may also have been involved in the making of the inscription. Unconfirmed reports also allege that he demonstrated a knowledge of runes while working on various building sites around the town of Brandon, shortly after he arrived in America in 1879. Ersk-Matsgården is just over 50 kilometres from Ohman’s birthplace as the crow flies, and it is scarcely too bold to imagine that he came across this variant of runes somewhere during his childhood.

At the same time, I do not believe that this type of runes was very well known; I suspect that they were reserved for a select few. At a time when elementary school education had become general and the vast majority were literate, some may have felt a need for a script that could not be immediately understood by everyone. This is where the Kensington runes come in. They should, by all appearances, be regarded as a partly newly created variant, based on runic traditions that have existed in different places in the Nordic countries in modern times. If we exclude the runes from Dalarna, which probably have a special history, they all seem to go back to the runic alphabet printed by the Magnus brothers in 1554 and 1555.

Knowledge of the runes was probably not very widespread in Hälsingland during the nineteenth century, as is also indirectly clear from the runes at Ersk-Matsgården. If it had been common knowledge in the late nineteenth century that the word diefvulen “devil” was written on the ceiling of the farmhand’s room, it would hardly have been allowed to remain there until the present day.

Magnus Källström is a runologist, associate professor and researcher in runic studies at the Swedish National Heritage Board.

- Many thanks to Anna Björk, not only for deciphering these inscriptions, but also for letting me use her photographs.

Other articles in English:

The Haverö runes – the key to the mystery of the Kensington Stone?

How the runes went from Hassela to Minnesota